Christmas is approaching, which for me and my brother began with our rite back in the 60s. We took out the sledge before Christmas Eve, and my father towed us to my grandfather. To this day, I can hear the crackling snow beneath his footsteps, and I can see the yellow lights in the windows of houses. My father, Imre Égerházi (who has since died in a tragic accident, exactly twenty years ago) is one of the few people who raise good thoughts in many, not just his own sons.

His life, which began on the second of September 1925, has its roots in much earlier centuries, as his pictorial ancestor, János Egerházi, created art in Transylvania in the 1600s. His works include the ceilings of Gábor Bethlen’s palaces in Alvincz and Gyulafehérvár, as well as the church in Gyulakuta.

This is one of the reasons why he, received a letter of nobility from Prince György Rákóczi II. Later ancestors arrived in Hajdúhadház with such a legacy, where the original possessors became more and more numerous due to frequent child blessings, so Imre Égerházi was already born into poverty.

“I didn’t see any painting at all until I went to school. In addition to the Bible and the Psalm, there were some calendars at home, a couple of youth novels that my father received at school” he recalls in his autobiography. It turns out that a packet of crayons, sent as a donation to their school by the Swiss Red Cross when he was only a 1st grader, brought a turning point in his life.

“I drew on the white walls of houses, on gray, dry boulders, on plank fences, everything I saw around me. I drew cow carts, old Uncle Szathmári, dogs, horses, houses in Szederjes, soldiers who sometimes practiced at the end of our street and the big, rarely seen cars. We repainted the houses, and I received a stick (and not the carrot) for everyone to see.”

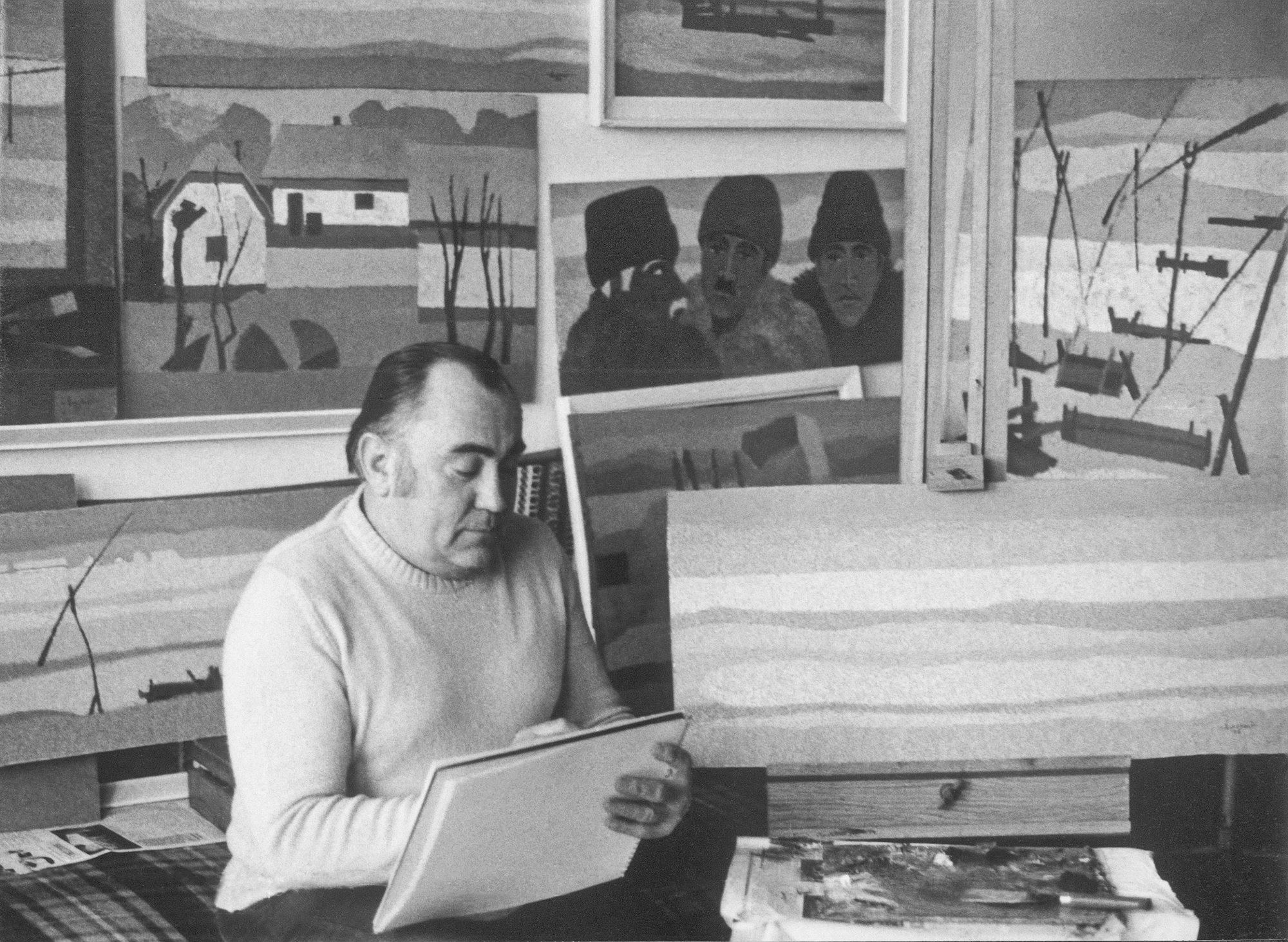

Of course, my grandfather was at the forefront of the rebuke, as he was always against the idea of his son becoming a painter. Although he was once a good student himself, he did manual labor for his livelihood, and he expected the same from his firstborn son. Nevertheless, Imre took every opportunity to learn the science of painting. After moving to Debrecen, if he saw anyone painting in the open air, he immediately stepped beside them to use the technique. He later joined them, and these influences left their mark on his work. His first master was László Balla, with whom he captured the Olajütő and the homesteads in Martinka and Nagycsere, close to the city, for a year.

Later, in the 50s, he met József Menyhárt at the Free School in Debrecen, whom he considered his chief teacher, and also learned woodcarving from him. At that time, in addition to his day job, he was able to indulge his passion. His family was there, so he did not give up this job even later, as a renown artist, due to a secure livelihood. The time and energy spent learning the craft finally realized itself in the form of a paired exhibition in 1963, joined with Rudolf Velényi, 15 years younger, at the Ady Endre Cultural House. His mentor, Menyhárt said the following at the opening ceremony:

“Not only does he paint with oil, but he also enjoys black and colour monotype solutions and also does linocuts. His themes are small streets around the residence, old houses, family life and still lifes. As the demand for himself and the ever-higher standard of artistic quality ensure the development, we will meet his name and his more and more valuable works every year.”

The master, sharing the fate of his protégé was right (none of them graduated from a school of fine arts and created art in addition to their day jobs), because in the next 38 years Imre Égerházi presented more than a 100 solo and about 400 group exhibitions around the world. He has received 21 state and professional awards.

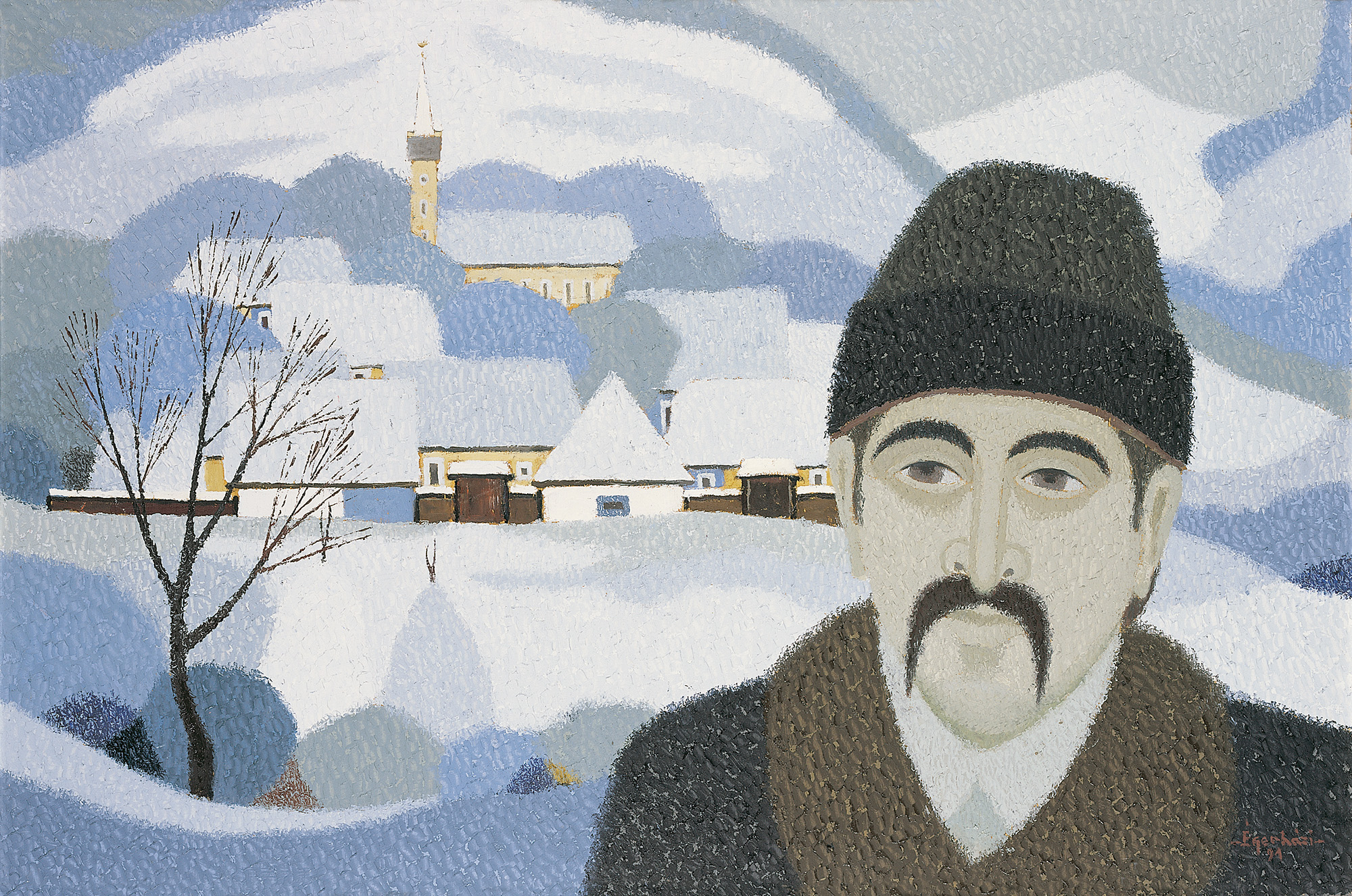

In addition to Hungarian settlements, his paintings were seen in many European countries, as well as in the United States and Japan. And what could be the secret of that? Perhaps the most authentic answer to this is given by art writer Ágoston Székelyhidi from 1978: „Égerházi, from a rural environment, arrived in the urban world, and thanks to these fundamental changes he became sensitive to differences between past and present, nature and civilization, or even to the amalgamation of these. This can be explained by the fact that he chooses his motives from a circle known to him, and he enriches and develops his approach and style organically and unbroken. At first glance, it is striking how much knowledge and experiential certainty he evokes in his paintings of the natural landscape with the structures and figures almost sprouting from it.”

Most of my father’s oeuvre is the painting of the Great Plain, Hortobágy and Transylvania, as well as the people living there, but he also painted several historical pictures and panels. Outstanding among the latter is a 6×4 meter work made in 1998 for the 400th anniversary of the Peace Treaty of Vervins. But how is a Hungarian artist invited to commemorate an important historical event for the French and the Spaniards?

The answer is simple, by which time he was already well known to art lovers in the Thiérache region of France, as he was honorary president of the Saint Michel colony of art, as well as the one at Bessans. However, he achieved all this not only with his works, but also with his work as an art organizer, with his system of international relations diligently established over the years, partly in foreign artists’ colonies.

To better understand this, it is worth jumping back in time, because as a son, I have witnessed from an early age how much he had the destiny people in his heart. He was the one to whom not only his close family, but also members of his wider social group could turn if they had to deal with some official affair, someone had to get a job or acquaintance, or maybe get proper medical care. Imre always solved it, or at least strived for it. It was no different when he tapped into the bloodstream of the art world, he quickly took the initiative.

He was only a founding member of the Hajdúböszörmény Artists’ Colony, which opened its doors in 1964, but the Hortobágy Creative Camp was reorganized under its leadership in 1982, and he held this position until his death. The artists’ colonies created a good opportunity to invite a multitude of artists, mainly Hungarians from abroad, to co-create. All this, at a time when, in Romania, for example, the authorities were even trying to restrict travel and were looking at every initiative in the mainland with suspiction.

But this did not deter my father from the intention to help,, and over time, like his relatives, the artists from across the border approached him with all kinds of requests and problems. Uncle Imre helped, he organized exhibitions, he did printing work, he tried to remedy their private problems, he organized trips, and who else knows what was included in the wishes.

Wondering if he was prayed for in 1988 when he had a heart attack and went into clinical death after the opening of the camp’s exhibition in Breda, Netherlands? He was revived twice by his fellow artists and once by the paramedics there, but he came back from the dead and painted his experiences – perhaps the only one in the world – in 11 paintings. In his vision, the bright being radiating unprecedented happiness sent him only one message: Wait! From this he understood that he still had work to do on Earth, and he lived on according to this, with a changed world of colours, with a sure faith in the creator, he continued to create and organize art.

Thinking about the future, he donated a part of his oeuvre to his hometown already in 1985, for which the settlement gave him a creative house, and in 1992 he was awarded the title of honorary citizen for the involvement of Hajdúhadház in artistic life. As if he felt that he donated 80 of his oeuvre to the Déri Museum in 1999, because he wanted them to delight their viewers. He continued to organize his artistic work with more attention to himself, living consciously, and he attended the rehabilitation sessions for those who had a heart attack, led by István Horváth and László Fésüs. Also where he tried to get on the early morning of November 14, 2001…

I hadn’t even left for the Debrecen editorial office when my phone rang. A police officer was asking for me, mysteriously just asking us to meet somewhere in person, so I recommended the Kálvin Square, near the office. Along the way, my thoughts rumbled in my head, as many times as a journalist, I was already searching for topics that were already writable or difficult to prove. But what the young man greeted me was overwhelming.

The conversation started strangely, he asked about my father, then he said that in the morning a long-distance bus hit him at a crossing on Füredi út, and he did not survive the accident. Time stopped, it was inconceivable to me that he was no more. I didn’t even know what to do with the thought for a long time, paralyzed; I just took the time to call my older and younger brother to relay the bad news. I spared them an hour and a half of unhappiness.

In addition to his creative house in Hajdúhadház, the gallery in Hortobágy bears his name, and since 2005 my brother and I have been rewarding one or two students per year at the Dóczy High School in Debrecen with the scholarship named after him.

Christmas is approaching, which for me and my brother began with our rite back in the 60s. We took out the sledge before Christmas Eve, because there were no Black Friday then, and my father towed us to my grandfather. To this day, I can hear the crackling snow beneath his footsteps, and I can see the yellow lights in the windows of houses. So we went for miles, while my father turned back and forth while telling tales, something he was particularly good at, and I can consider myself lucky, have been brought up on his stories. My journalist colleagues, too, could hardly be overwhelmed by how good it was to talk to him, how impressively he could storytell.

The trip back with the sledge was also hastened by collecting all needed for a good Christmas and having the grandparents join us. At home, my brother and I had to wait a few more minutes in the hall of the one-room apartment until the bell rang, indicating that Jesus had visited us. And for the last 20 years, it rang for my father…