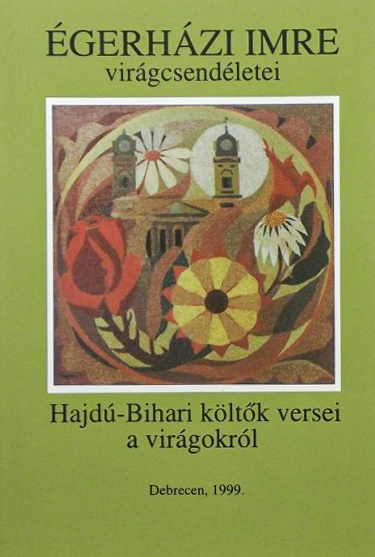

Flower still lifes of Imre Égerházi

The painter and his world

“Painting is poetry without words, poetry is painting with words”

I never felt this quote, by Simonides of Ceos, truer than in relation with the still lifes of Imre Égerházi. These works of art are warm, sensitive, intimate elegies when formulated in the language of poetry. Far from them is the rhapsody, the ode, the anthem, the ballad, the epigram, the epic, and maybe approached by the lyrical song of fine purity. The flowers of Égerházi are never loud, they do not flutter, the background does not dazzle, but the image is formed from a peculiarly personal mixture of brown, green and yellow, somewhat symbolizing the autumn atmosphere of eternal passage, and the ever-renewing spring. They are beautiful in the original sense of the word, whether they are concrete recognizable flowers in the painting, or more abstract, translucent color variations that explore the essence of “being a flower”. It was the painter’s idea to put poetry in addition to these still lifes. In addition to the paintings inspired by the landscape, the poems of the natives of and the creators from the landscape are connected here.

There is no question, then, that these paintings were born in the inspiration of the poems, but there is no question that the images specifically touched the poets at the time the poem was born. The whim of the editor put them side by side. With the intention that both the painter and the poet could tell why he considers the flower a theme in his art.

The images and poems were created independently, but the editor felt they had something to do with each other. There is an emotional and intellectual connection that makes their appearance together natural.

Goya says, “Painting, just like poetry, selects from the universe what best suits its purpose.”

What is this goal? Exploring the secrets of existence as deeply as possible, understanding the relationship between man and the world, finding and presenting beauty.

The prominence of beauty made painting more lyrical, bringing poetry and pictorial art closer together. Think about it, Rimbaud tried to define the basic units of the spoken language, the phonemes, with colors: “Tar for A! Snow for E! Red for I! Green for U! Blue for O! – only once / can I be brave enough to tell all your secrets!”

Aragon also speaks very beautifully about the relationship between poetry and painting: “I reveal the scent of the seeming figures / I reveal why the snow-coloured paper sings / I reveal what gives lightness to the foliage / And to the branch that bends slowly like a rocking arm.” Here could stand some of the true and beautiful thoughts of István Szőnyi about the relationship between colours and scents, also.

The fine lyricism is strong in the painting of Imre Égerházi. Especially in his still lifes. In this peculiar genre of painting, which – after the additional floral elements of the Renaissance and the motifs and ornamental decorations of ancient Eastern painting – unfolded essentially in 17th century Dutch painting. Then he took a dazzling historical journey. From Chardin to Delacroix, the road continues through the art of Corinth, Manet, Monet, Rodin, Cézanne, Van Gogh to this day (and this is only a tangential example.)

Still life is very often used by painters to conjure a lavish flood of colour on canvas. Thus used, for example, our Munkácsy and László Holló, whose flower still lifes were first published in an independent volume in Debrecen with the folk song collections of János Papp, courtesy of Professor Zoltán Ujváry, in 1972. Why is flower still life a suitable genre to project the artist’s emotional world? Because it is about life, but at the same time it tears the theme out of nature. In some languages, still life is called “dead nature” (e.g. in Italian, “natura morta”), also expressing that the world of nature is consciously placed in a different space. Nature is present, but as if time has stopped around the snatched motif. I think Égerházi wanted something like that with his still lifes; to stop time, to seize fleeting beauty, to face transience. Only few of the flower stills have a petal or flower head fallen on the table.

His still lifes do not show the lawfulness of passing, nor the loud triumph of existence, but the quiet serenity, the subtle beauties, the stopped moment.

In this way, a clock symbolizing time, a pear referring to ripe nature, a beautiful female face, the much-loved Transylvanian landscape, or symbolic motifs of Hungarian folk art can be built among the flowers.

Égerházi also found a technique for this atmosphere. Most of the still lifes are monotype (in addition to pastels and oil paintings), the imaging of oil paint on glass or sheet metal on wet paper preserves the characteristics of the graphics and the possibilities of painting.

Translucent delicacy, loose contours live on the images, creating a bit of a mystical relationship between creator and object, flower and man. I also tried to choose from the poems those that carry the marks of delicacy, wise serenity, translucent beauty in their mood. Keeping in mind Vincent van Gogh’s words that can be treated as law: “I am not looking for the appearance, but for the essence, that which lies behind the phenomena, that which is the secret of life.” Perhaps the images and poems together will not only be a meeting of the painter and poets, but will also mean that readers and viewers will become part of the wonderful circuit they call art.

József Bényei