I was born in “Miglahac”, Kis új street, in Hajdúhadház, on September 2, 1925, 5 PM, as the firstborn of the family. We lived on the middle of the street in a earthy little house, waiting to collapse. One night a cat pushed my father’s boots and he, hearing the thump, picked me up, cradle and all, and escaped to the yard as he feared the house is coming down on us finally. My parents have deep roots in Hajdúhadház. In History of Hajdúhadház (by dr. Sándor Nagy, 1928) there is a report about the status of the settlement from 1783. “Owners by matrimonial law. Residents of inner yard, 3 tenths, from families István Égerházi, Barna Szabó.” The family of my mother’s, Erzsébet Péntek, is one of the oldest in Hajdúhadház. I donated a mouse-ridden family “dog skin,” owned beforehand by Mariska Nagy Béláné Égerházi, to the Debrecen archives, where they filed and restored it and sent me some photos.

In the letter of nobility, given to my family by Mihály Apafy on December 6, 1670 states: Mihály Bősházi Égerházi “raised from serfdom… truly and undoubtedly ranked among the nobles of Transylvania and the connected parts of Hungary… with our decision Mihály Égerházi and all his descendants are considered noblemen…”

Description of the family crest: “blue shield, in its lower field an arm of a man, oriented right, holding a green laurel branch. In the center of the field a waving ribbon with the inscription: For art and homeland.”

Among the 11 (nobiles advonal) newcomers Égerházi is already mentioned. It is possible they made it to Hajdúhadház much earlier. Resettlement happened in 1605. The letter of nobility of Hajdús was given by Bocskai. Mihály Égerházi received it from Apafy in 1670. Possibly their ancestors are related to the Égerházis of Mezőbánd, described in Art History Studies (by Lajos Kelemen, Kriterion, 1977). A member of this family was János Égerházi, or “Képíró” (an archaic word for painter). The young nobleman János Égerházi worked for prince Gabriel Behtlen. He painted the ceilings of the Alvincz and Gyulafehérvár ducal castles, and the reformed church of Gyulahuta. He and his brother, István, was re-nobilized by him and were given a crest, on it a knight rides a turul bird above three heaps. In his left hand he holds a sword with a decapitated Turkish head on its tip. In his right hand he holds a palette and some brushes. On the top an inscription: Qvod libet licet.

Without any doubt we have ancestors of well-known artists. (A much detailed research would be needed to completely discover the lineage.) I never seen a painting before my primary school years. In our hose, besides the Bible and psalms, we had some calendars and youth novels, given to my father as a gift. Some of those I re-binded (as I learned bookbinding in the civic school) and treasure them to this day (poems by Sándor Petőfi and Mihály Tompa, Egy magyar testőr by Mózes Gaál, the life of Francis II Rákóczi and Lajos Kossuth, The Last of the Mohicans, The Deerslayer). This is how I preserve the wonderful tales and stories of Uncle Dani Tatár, which we listened to while sitting at the foot of the fence in the evenings.

I was already a schoolboy when one time we brought ‘luthur’ and ‘porcsin’ from the Gábor garden with Andor, one of the waifs of Mari Juhász. Coming home looking through an open window, I saw a very nice painting in a thick brown frame. Rákóczi says goodbye to his wife and children. (I now know it was a color paper print.) I just stood by the window and, like the bewitched, I looked at the painting. Rákóczi and Ilona Zrínyi were old acquaintances of mine. My father read a lot about them, especially in the evenings, and when the story was heartbreaking, he breathed so deeply that the lamp on the little blue pot almost went out, and shed tears for the saddest ones.

I received a box of colored chalk from my first grade teacher, József Szabó, as a gift from the Swiss Red Cross. Everyone got something different, better than me, and no one wanted to switch with me. I drew with it on the white walls of the houses, on gray dry ‘berena’, what I saw that was around me. A cow cart, Uncle István Szathmári, dogs, horses, houses rocking in Szederjes, soldiers who sometimes go to practice at the end of our street, and cars that rarely show up. We re-painted the houses, and I got “the end of a stick” as a reward.

In my first drawing memories, there is a lot of joy in “creation” because they recognized “Gergely who can saw”, the rushing fool of the village, the “Wild Boar” gypsy, the Sinka who stole the wood. By the time the chalk ran out, I had made an eternal friendship with drawing. Later, I also messed up the walls with a soaked, soft piece of brick. Once the Dudinsky shopkeeper caught me and yanked me into his shop. Squeezed on a stinking barrel, he threatened to suffocate me if I continued to scribble and toss stones into the hole in the firewall. I was very scared then, but the scare only lasted for a short time, because going on I grabbed the bell of the nearby blacksmith and ran away. I went to the “crap” elementary (Reformed) school. At that time we were still sorted by our knowledge. I was always third in the classes of teachers Szabó, Csősz, Csiha and Varró. The first was Tibor Szentkirályi, the second was László Hadházi. We wrote on a chalkboard with a slate pen, which we sharpened on the stone feet of the building. I really liked going to school. At the north end of the west side of the school building was an approx. five by five meter, very thick wall. The ruin was maybe one meter high (according to the elders, a remnant of the old church). We played this Turkish-Hungarian, Kuruc-Labanc war. I was always Hungarian in the game. I would rather not play if I couldn’t be Hungarian.

My father was an agricultural worker, a field worker, a printing worker, because we could not make a living from the little inherited land and vineyards. Before moving to Debrecen, he did manual labor at Müller’s Erzsébet Steam Mill (hired by Miksa Stein). If school was over before I even had lunch, I had to take the food to the mill. My father sat up on top of the stairs to the hopper and ate there. I waited excitedly for the leftovers. He always left a little of everything. I haven’t eaten anything better since. If I had to wait any longer, I sat on the bench in front of the mill. Two farmers, Imre Hajdú and Sándor Tatár, usually farmed here. Sometimes also Mr. Stein, who once gave change, which I spent on sugar in the Bihari store. The mill was far away, I got home tired. I still had a lot of work to do at home. Learning was left for the evening.

My father went back to the railroad, the old place where he was B-listed. We barely attended the fourth grade when we moved to Debrecen in 1936. We cried all the way to the top of the chariot down the street. We reached the ticket house (customs house) in Debrecen, turned left, and arrived in one of the streets at the end of the city, which was just as dusty and poor as the one we had left. It was a big disappointment for me. I was enrolled in the Csapókerti school. My teacher was Gyula Sinai Hórebhegyi, who played beautifully. I soon became one of the firsts. We weren’t sorted by knowledge here. In the fifth grade, Mihály Bakóczi taught me, who appreciated and loved folk kitchens and those in testvércipő. At the encouragement of one of my classmates, János Németi, since he thought I had beautiful writing and drew well, I wrote it with red chalk on the blackboard: proletarians of the world, unite. All I knew about its meaning was the motto of the Communists. Teacher Bakóczi wiped it in horror, without a word, and when I confessed that I did it, he asked; where your father works. At the railroad press, I replied. Then at the age of twenty, ask me what I want to say now. In September 1945, I asked. He replied, it is not timely.

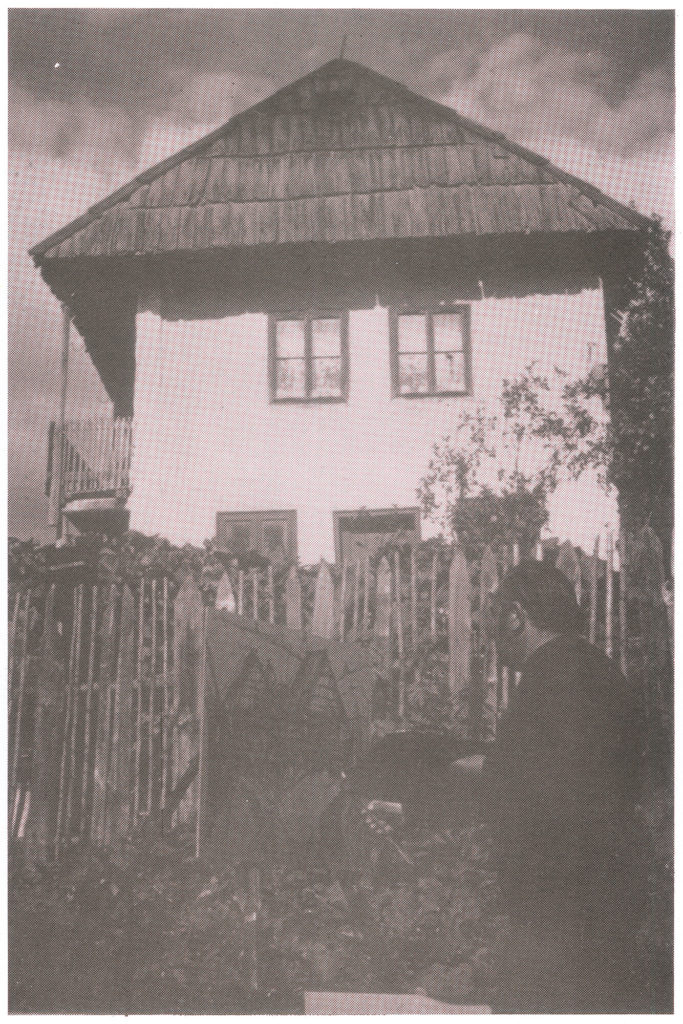

We lived in several places and then settled permanently in Báthori Street. It was a flea’s end. There was also a good side to this move to Debrecen. The best part is that I was able to go to the Déri Museum after church on Sunday mornings. Even today, I can tell you the order of the paintings on the upper floor. It was also possible to bathe for free in the ditch draining of the heat spring water. There, a gypsy man sang arias and pan-handled. It was possible to go to the Meteor cinema for squeezing sunflower peel. In the summer, my brother Sándor and I went to the tennis courts to pick up balls. When we lived on Apafája Street, in the penultimate house, in front of the infinite border, I could see people painting in nature. Under the trees of the Diószegi farm, a thin, spectacular painter (Ferenc Nagy) painted oil paintings on the nearby farm. Like the shadow, I followed, and while he worked, I always lingered beside him. I did not go to school. In Matthias King Street, sitting on a small chair, on a dwarf stand, a part of the street was painted by a fat bald painter (László Balla). Years later, I learned editing and oil techniques from him. In one year we painted the Olajütő all spring and summer, and in the autumn we painted the farms in Cserei, Martinka. My father brought papers and lead pieces from the press. I drew with these and painted with watercolor.

At the age of five, a classmate of mine, my father Sándor Csige, died of lung disease. From my little stuffed money, my Easter “earnings,” I bought his father’s “set” of oil paint, some shabby brushes, and a thin tube of paint. I was infinitely happy with the paints. I happily absorbed the smell of oil paint. To always be able to feel it, I squeezed a little of the Van Dyk brown in my left palm and smelled it all day. I put a different color on my palm every day. I was reluctant to wash my hands, even to my parents’ urging. I did not know how to use the paint.

I was trying to paint on a deck of paper, and failed. I wasn’t bitter, I knew it would work for me. I really wanted to learn more. My teacher also encouraged me. I wanted to go to college. However, my father decided to send me at the cheaper civic school in Hajdúhadház. What I’ve been most interested over the years is whether or not I’ve gotten tuition exemption. The walkout was very tiring, especially as the war developed. If the trains weren’t running or they were very late, I was with one relative or the other. I had a very hard life. I liked to go home because in the station building, in one of the rooms, the station boss (Mihály Tóth who is etsei but called Tóth) painted. I missed several trains because I couldn’t break away from the window. He copied mostly classics, and I was able to follow every moment of the copying.

When I once told him later how much I had learned from him, he didn’t want to believe it. On another occasion, one of my classmates, who lived next to Szederjes (Gerzson Szikszai), called me over once. His brother painted an organ still. I watched in amazement as he mixes the colors, how he puts them on canvas.

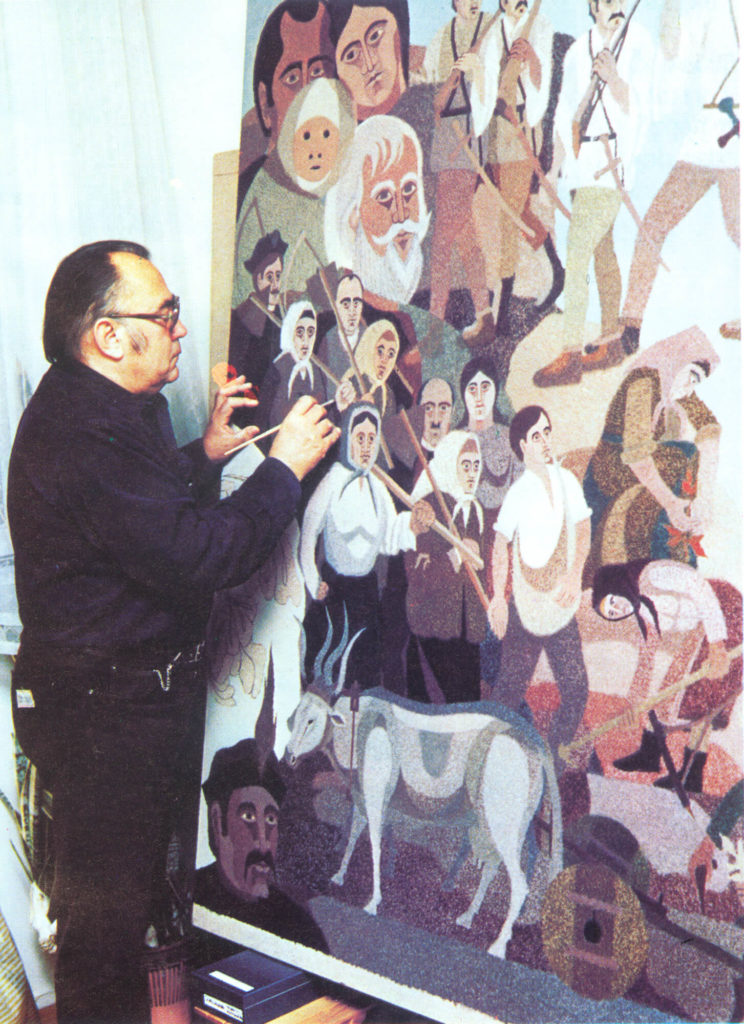

We drew a lot in civic school. I liked double drawing lessons and art history the most. Once in a school competition (it had a motto) I won all the first three places. I loved to draw and paint in the girls’ memoir. Even now, I am sorry that there were no specialties then. As civic schoolchildren, we took part in the big Hajdú celebration in Hajdúböszörmény. It was a wonderfully uplifting feeling. There, in Hajdúböszörmény, I decided to paint a picture of the Hajdús. This topic has occupied me all my life. I also drew many times. I had ideas that didn’t materialize, but I couldn’t give the topic a rest.

Towards the end of the civic school, I suggested that I would like to go to a painting school in Budapest. My father, who was color blind, passionately protested against my plan. He was material and referred to his wish for a better fate for me. At the beginning of the great world burning, Polish refugees came by train. We had a small vineyard in Vénkert at the outside marker. Such an assembly was not allowed into the station. Men, women, children and soldiers jumped off the train. They took the fruit from the trees, shattered the pumpkins, and ate it. Some ran to us, “pani-pani”, they said, and pointed at their mouths. One quickly drew my father along with the barn in a drawing book. All our leftovers were given away. You see, my father said, it’s so inanimate that it can’t even steal. These freeloaders are all like that. Due to the drizzling rain, the drawing remained in the barn. The next time we went, there was no door on it. This opportunity was also used by my father to talk me out of my plan. He opposed not only studying in Pest, but also drawing and painting in general. Many years later, however, he befriended the concept when two halls of the village council of Hajdúhadház were emptied and my exhibition was held there (1973). But mostly because I also had a “regular” occupation.

After graduating from civic school, I was a day laborer at a construction site next to the masons. In September, I was looking at school goers with teary eyes from the floor of a house under construction on Baross Street. During the winter I applied for a post office junior in Kassa. In March 1942 I was taken to the prince’s city. At least fifty from all parts of the country and the reclaimed areas. We could go out into town in the afternoon. After such a Museum-Dome visit, I saw a dwarf painting on Vársánc Street. He was sitting in a small chair, painting a watercolor picture of a part of the street. He was Lajos Feld. I was always there at the agreed place and time and watched him work, if I was able. We later became friends and corrected my weak aquarelles with kind love. He spoke very little, he was an aloof man. During the war, he became a draftsman of Mengele, so he escaped death. After the liberation, I went to work with Social Security office. Here, too, I always painted in my free time. I copied the classics and others. I was happy to paint the experiences of my childhood. The animal fair at Vadas. The summers returning home at dusk, the lumberjacks going to and working in the woods, warming up by the fire. I painted several pictures about Francis II. Rákóczi, whom I loved very much and still love today.

In the 1950s, the Debrecen Free School operated on the ground floor of the Piarist High School. I’ve been here before. My teachers were Géza Veres, László Balla, József Menyhárt and László Félegyházi. Because of my busy schedule, I couldn’t go for long. Later, a painter named Balogh Kőrösi taught some of us in the decoration room of the SZTK among the pictures and banners of Rákosi, Stalin, Lenin I painted. It didn’t last long, and I didn’t take much out of it. Lajos Bíró also gave a lot of useful advice in the 60s. I continued to visit the exhibition halls and museums, especially the Medgyessy Hall of the Picture Gallery, where I was an everyday guest at the same time (Dr. Ottó Bába still mentions me to this day).

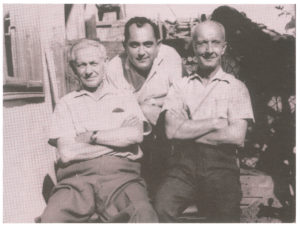

I also met László Holló, with whom I spent many beautiful days that were useful to me. His art, his picturesque demeanor, his pure humanity left a deep imprint on me. Only the time spent with Uncle Imre Nagy in Csík, Zsögöd is more memorable. Somewhere, sometimes between the rows of vines, sometimes between his pictures, sometimes soaked in boron water up to his neck in the concrete tub of the Zögöd bath, I listened to his explanations about the fate of the world, art, vocation, beautiful women, wonderful stories.

Once my paintings in my office room were spotted by Mrs. Andorné Király, a drawing teacher at Dóczi, and based on these, she recommended me to the patronage of József Menyhárt, who tirelessly taught me all the ins and outs of painting and graphics. He gave and recommended books. On his recommendation, I studied the college notes and recommended literature. Over the years, a true friendship has developed between us. He was my true teaching master and paternal friend. We had a similar fate. Neither of us graduated from the College of Fine Arts, and we both worked in offices, after 8 hours of intellectual work a day, we painted in our spare time.

I was always very sorry that there was no drawing major in the four-year evening course of the high school of business. After a giant detour, I was well past 30 years old when I first exhibited with amateurs and later with professional painters.

Fate was gracious to me. I became a founding member of the Hajdúság International Artists’ Colony in Hajdúböszörmény, where, I feel, I became a painter. Since 1982 I have been running the creative camp in Hortobágy, maintained by Cívis Rt.

During my life-trying periods (when I returned home in early 1945 after experiencing the siege of Budapest and was sent to the Balkányi estate in Nyírmártonfalva with other people waiting for “verification”, when I was listed as politically unreliable by the Post Office in 1946. , when excluded from the MDP because I was declared “right-wing,” when I became “noted” in 1956 because I was a member of the Workers’ Council of the SZTK and the General Assembly of the County Revolutionary Committee) painting, drawing, engraving always helped. It was during these times that paintings were born that were never shown anywhere (Hesitant to Enter, The Mourning Day, Devotee, Land Distribution, Liberation of Women). I made my cherished dream come true for decades when, based on a sketch made on paper on 17 February, 1984, I completed the 185 × 600 cm panneau entitled Hajdúk, in 30 June, 1987, which shows their lives until 1896. I planned to present the further fate of theirs by painting Hajdúk II., a 200 × 300 cm artwork.