Painter and his world

Every person has as much of the world as they can notice, see, get to know from it. The blessed gift of the artist is that their vision is much greater than that of a layman blessed with the greatest thirst for knowledge. They notice the wonders of detail. It is also a blessed gift to see not only the elements of reality, but also the secrets of the inner world appear on his retina. As well as being able to show the elements of the world seen outside and inside. And this vision already means a new order, a fuller and truer world, in which the laws of harmonies and disharmonies are given not only by the objective reality of existence, but also by the mysterious secrets of the soul. That’s why donkeys and sad old Jewish violinists can fly in the wide-open space, that’s why the yellow wave of sunflowers can cover everything, that’s why they can spread time to dry, that’s why the light of Lake Balaton can splash over everything.

Imre Égerházi got to know a very wide part of the world. In his paintings the objects and elements of rural poverty, the children’s visions of the suburbs, the peculiarities of the Bulgarian, Polish and French landscapes, the characteristics of the streets and houses of Hajdúság, the many transcendent elements of the infinity of Hortobágy, as well as the greats of art and literature. And all this is present in such a way that they can be recognized in their material reality, but at the same time it is not the concrete reality that binds, captures, but the inner harmony radiated on the screens of the atmosphere, mood, imagination and soul.

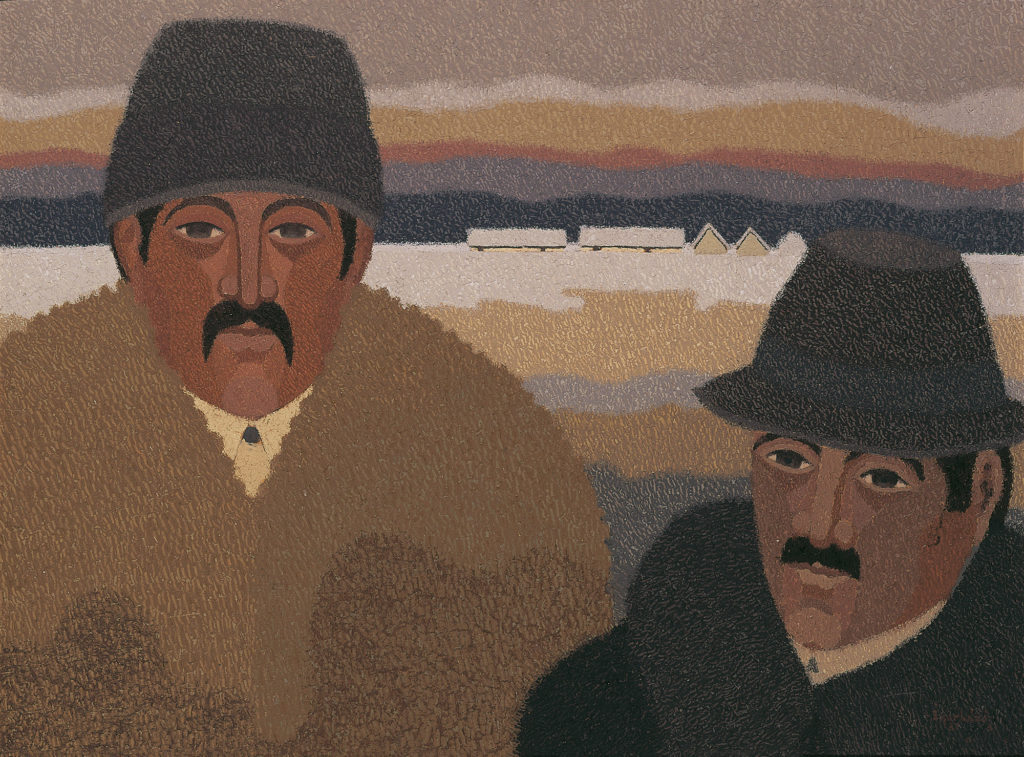

I think the first and most important element of Imre Égerházi’s world is this magic. Transcendence. Respecting and clinging to specific elements of reality with the heavy allegiance of childhood, but at the same time at the stations of his artistic development, increasingly elevates this reality to another world beyond the earth, of ethereal purity and beauty: the painter’s own spirituality. Égerházi loves his objects. He only paints what he has a personal connection with, which triggers the miracle of recognition from him, so he can also recognize us as spells of hidden beauties. I think that the best of his oeuvre are the images of Hajdúság and Transylvania, which show the slices of the world he has seen and reinterpreted with balladistic conciseness, but at the same time with the subtle atmosphere of poetic elegy.

Where does this magic come from? Stendhal said painting is just morality created. I think one of the elementary sources of Égerházi’s art is his life journey. With rigid consistency he learned without schools, and more than schools can teach. He learned all of the craft, sometimes perching with stray painters, sometimes with the hope of the excluded inside the window, sometimes consciously. This is the moral mentality: the desire for the fullest possible cognition is a decisive moment in his oeuvre. Because this rigid consistency has shaped his relationship with the world. His loyalty to his people, to the Hajdús, to the ancestors of Transylvania, whose genes had to make their journey into his hands, through centuries. This unquestioning attachment, with which he grew his retaining roots inside the time, led to the characteristic Hajdúság depiction of houses, people, faces, trees, animals. The restrained warmth of his colors, the often praised consistency of his compositions, and the special interpretation of space made it possible for his oeuvre to comply with the moral laws of loyalty, honesty and attachment. Somehow, as the standards of Pál Gyulai, János Horváth or János Barta demanded this of all art.

We must also talk about the rigid ‘Hungarianism’ of Imre Égerházi. Let’s look, for example, at the Polish landscape, where he has almost reached the extreme degree of abstraction and yet it radiates there, the grooves and tiny spots of the Hungarian land shine there. He expresses this Hungarianism not only in his paintings, which are built on the motifs of Hungarian folk art or the Hungarian past. It is a kind of Hungarianism like Miklós Káplár’s or László Holló’s (without its tragic overtones). Infinity, the sheer, the boundless view of the landscape, even if it is confined within the boundaries of lines, almost enlivens and nourishes this patriotism. No matter where he goes, to Bulgaria, France, Poland, he sees and creates that he is Hungarian in essence.

Another important element of his particular art world is that he unmistakably recognizes the essence. Recognizes and highlights. Be it a water bottle, a face, a house, a black gate from Böszörmény, let there be horses from Hortobágy leaning over the spikes, let there be a mountain house in Gheorgheni, this essential element is one of the basic elements of Égerház’s compositional skills. Sometimes he surrounds the pictorial essence with motives, but only to guide our eyes more securely to the most important. Only a creator who knows and respects reality in every detail can create this. And maybe that’s why we can say about his pictures: he not only gives back the landscape, the seen reality on them, but the soul of the landscape. Inner essence.

At the same time, everything is completely ostentatious. It does not sparkle your drawing skills or craftsmanship, they are so naturally present that they do not even appear separately. Restraint can also be seen in the way he treats colors. Almost every image has a leading hue, a compositional, essence-highlighting lead color, which is then surrounded by spots of harmonized color variations. There are no huge tensions, no loudness prevails, the warm serenity of the colors causes us to feel in front of his pictures like the shepherd of Hortobágy, who crouches by the small fire on warm frosty evenings to warm his hands. This inner warmth flows from his pictures of Égerházi. Humanity? Serenity? Calmness? Maybe all. The joy of the soul over and above the creation, when it was noticed, could show all the beauty that created harmony in the soul of the creator.

This restraint, this inner harmony is also expressed in the fact that there is hardly any movement in Imre Égerházi’s paintings. Horses do not run, the sky does not lightning, wild geese do not fly, old chariots do not pound. It is a seemingly static world, but it is not, because on the one hand the juxtaposition of objects, on the other the conscious arrangement of colors and shapes, the order of oval or square lines, or something unusual creates a different kind of dynamics.

Let us remember only his painting depicting boom wells in Hortobágy, where interlocking well booms, or his painting Memories of Our Past, where a sloping yoke, Tanya, where the curved trees placed in the foreground create an unheardly delicate yet powerful dynamic of the image. Based on all this, I dare say when I look for poetic parallels as a result of my work, that Imre Égerházi’s paintings – although undoubtedly with balladistic conciseness and intermittency – are most reminiscent of elegy as a poetic genre. The translucent delicacy when one sees his own breath in front of his mouth at winter dawn is the flash-like charm of a bouncing fish showing its silver belly in the river, yes, that is his quite characteristic elegiac dynamics. This element is present in almost all of his paintings, which is why, despite all the constructivist details, I can relate the paintings of Imre Égerházi to the late elegy of Árpád Tóth:

“Mint a bokrok setét bogyókkal,

A hó alatt zamatozókkal,

Megrakva szívem hűvös jókkal.”

There should be many more elements of Égerházi’s art, such as its consistent compositional order, the conscious application of color spots and geometric lines, or the specific plane formation in which it places the object of its paintings. However, these were often seen and written by others. I would rather be talking about another element that I am also not discovering, but perhaps needs to be defined by stronger features. This is Égerházi’s special, quite unique modernity. Why is it special? Because it comes from the re-creation and rewording of elements that form a specific, original unity in his paintings.

For example, it is not uncommon for someone to turn to the sources of folk art. However, Égerházi is not satisfied with the transfer of certain entographic elements and objects to some of his paintings.

He also knows and applies the spirit of folk art, the most ancient folk tradition. Let’s look at the eyes in his portraits, for example. Let’s say the eyes of the figures of the Shepherds, the Stallion and his wife, the world of Krúdy, or the great composition, the Hajdús. This is the same representation of the eyes as that of the ancient Native American arts, so perhaps it seems that a deep well of time is leaking out of these eyes. The same timeless depth is shown by the simplified forms of houses, gates and trees used in folk art.

It might not be so original so far. True originality begins there when it combines this folk art heritage, this universal cultural treasure, with one of the characteristic styles of the turn of the century, one of the characteristic styles of the turn of the century, Art Nouveau. He gets the least from this totality in his works, in which the alloy is very conscious (for example, Still Life in the Studio, Flower Still Life, etc.). and his pictures of Transylvania, in which Imre Égerházi’s career reached its peak.

And surely, all cannot be mentioned in this short introduction. For example, about his extremely rich, very lively graphics or his work as an art organizer, indelible traces of which are preserved in strong documents in this very landscape. But now we wanted to greet the painter. The 70-year old painter, who, knowing his career so far, will certainly go even further into the consistencies of his own choice, we hope that many times we will stop by Imre Égerházi’s bright pastoral fires to warm our hearts and hands at his human and artistic purity.

József Bényei